Hiring is often described as a strategic role, yet many interview processes feel anything but strategic. Despite the abundance of tools, research, and guidance available, organizations still create hiring experiences that frustrate candidates. These processes waste time. They quietly erode trust.

This article takes a reverse approach. Instead of explaining how to interview well, it tells you how to be a bad interviewer. It does this efficiently, consistently, and with remarkable confidence. If any of the scenarios below feel familiar, that’s not coincidence. It’s recognition.

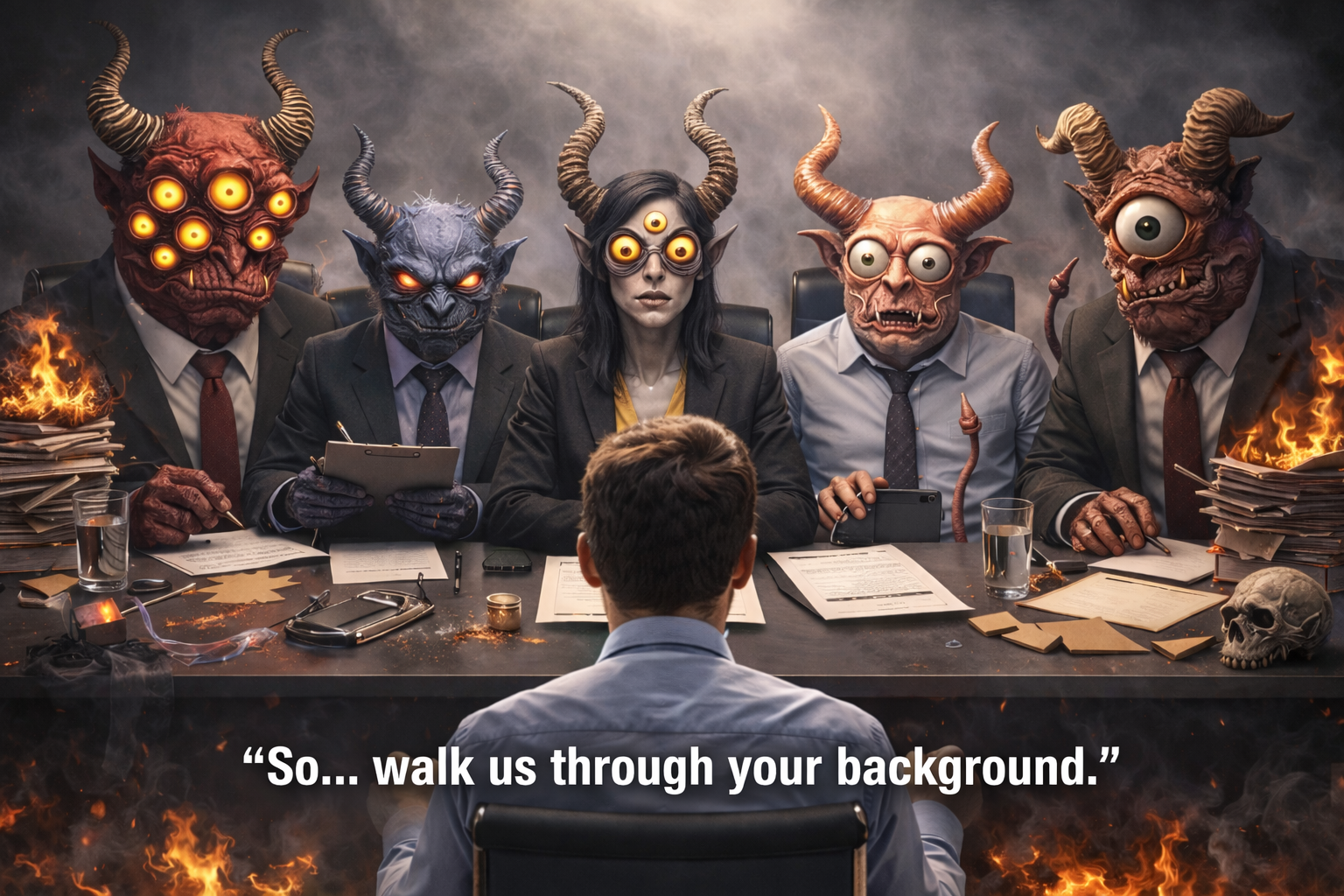

Arriving Unprepared and Ignoring the CV

A truly bad interview starts with a bold move: not reading the CV. The interviewer opens the meeting with, “So, walk me through your background.” It seems as if this information has just been discovered moments ago.

This approach communicates something important. It tells the candidate that their preparation was mandatory, while the interviewer’s was optional. It also quietly asks the candidate to carry out unpaid narration of a document that already exists. This task was not requested by anyone. Still, it is endured by everyone.

Repeating the Same Information Until It Loses Meaning

Nothing says “well-designed process” like asking for the same information four times in four different formats. The CV covers it. The application form repeats it. The interview revisits it. The onboarding document asks again just in case reality changed overnight.

At best, this signals inefficiency. At worst, it suggests that no one involved in the process talks to each other. Either way, candidates quickly learn that clarity and cohesion are not organizational strengths.

Keeping the Role Mysterious for No Good Reason

Bad interviewers understand the power of ambiguity. Job roles are described in abstract terms that sound impressive but mean very little. Phrases like “dynamic environment” and “wearing many hats” do the heavy lifting, while actual responsibilities stay conveniently undefined.

Salary discussions are avoided as though they are taboo, and questions about structure or expectations are met with polite deflection. Candidates are expected to commit to uncertainty enthusiastically, because apparently clarity is a sign of poor attitude.

Treating Time as a Suggestion, Not a Commitment

A hallmark of a bad interview process is casual disrespect for time. Interviews start late. Calendars change suddenly. Candidates wait in virtual rooms, refreshing screens. They wonder whether the interview is happening. They question if they have entered an endurance test.

Candidates have taken leave, arranged transport, or rescheduled commitments to attend. But this is rarely acknowledged. After all, urgency is something candidates should have, not interviewers.

Asking Questions That Should Never Be Asked

Some interviews drift effortlessly into inappropriate territory. Questions about age, family plans, or personal beliefs often casually, framed as harmless curiosity or small talk.

Even when no harm is intended, the effect is the same. Candidates become guarded, trust erodes, and professionalism takes a back seat. The interview becomes less about suitability for the role and more about navigating discomfort politely.

Turning a Conversation into an Interrogation

In a bad interview, balance is unnecessary. The interviewer dominates the discussion, interrupts freely, and leaves little room for the candidate to ask meaningful questions. Information about the company is scarce, but judgment is plentiful.

The underlying message is clear: the candidate should prove their worth, while the organization remains unquestioned. Ironically, this approach tends to repel candidates who are confident, capable, and accustomed to mutual respect.

Demanding Free Work to Test “Commitment”

No bad interview process is finished without an unpaid assignment. Candidates are given tasks that closely resemble real business problems and need significant time and effort. These tasks are described as small, quick, and necessary despite evidence to the contrary.

Feedback is optional. Follow-up is rare. Compensation is nonexistent. Candidates are left wondering whether they were being evaluated or simply crowd-sourced.

Disappearing Without Explanation

After weeks of interviews and assessments, silence sets in. Emails go unanswered. Messages stay unread. The process simply dissolves.

Candidates are left guessing whether the role was filled, paused, or abandoned entirely. Ghosting becomes the final, unmistakable confirmation that professionalism ended somewhere around the second interview.

Blaming Candidates for the Fallout

When candidates withdraw or express dissatisfaction, the conclusion is swift: they lacked patience, resilience, or commitment. The possibility that the process itself is flawed is never seriously considered.

This mindset is comforting, but costly. It ensures that nothing improves, while the same complaints resurface in every hiring cycle.

Publicly Wondering Where All the Talent Went

The final act is familiar. Companies take to public platforms to lament the shortage of good talent and question the work ethic of modern professionals.

What often goes unmentioned is that capable candidates were there. They simply paid attention and opted out.

Closing Reflection

Bad interviews don’t just fail to attract talent they actively teach capable people to walk away.

If hiring feels like a power exercise instead of a shared evaluation, don’t worry ,you’re not losing talent. You’re training it to avoid you.